Cecilio Pla y Gallardo

Ladies in the Garden

c. 1910-

Oil on canvas

42.1 x 66.4 cm

CTB.1997.93

-

© Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza en préstamo gratuito al Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga

Around 1900, Cecilio Pla adopted a bright and gentle style of painting then being promoted by Valencian artists, particularly after the appearance of Sorolla and his rise to international fame. Brightness would come to be one of the most deeply defining features of the new Valencian painting and paved the way for artistic regionalism. Fortuny, Rosales, the Impressionists and even Northern European and Italian artists were prominent figures among this group of painters obsessed with light, whose vitality and sensuousness are usually contrasted with the more sombre and grey visions of other Spanish artists of the time. However, Cecilio Pla’s concept of painting and sense of colour and light should not be seen exclusively as an expression of the Valencian school, for he moved to Madrid while still very young, although he did maintain the connection with Valencia through his master and friend Emilio Sala, a painter with a cosmopolitan outlook (whom he did not surpass as a portraitist). It was, therefore, more of a shared attitude that Mediterranean painters seemed to cultivate to its highest degree. In works devoted to social issues such as Midday(1891), now in the Museo del Prado, a dazzling light emerges from the background, even though the main scene unfolds in shadow. By the late 19th century, Pla’s landscapes were chiefly inspired by views of northern Spain, above all Asturias, where he often visited his friend Casto Plasencia. Despite such circumstances, the effects and presence of sunlight would gradually take on greater importance in his works after 1900, and particularly after 1910, when brightness is emphasised in his landscapes. This is especially evident in the vibrant scenes of Valencian beaches that would soon reveal his indebtedness to Sorolla, although in his personal development, he would never waver.

Ladies in the Garden belongs to that moment of luminarist plenitude that intensified after 1910 and is even present in Pla's portraits, many of which have an out-of-doors setting. Despite the hustle and bustle in his sketches, his vision is usually sincere and serene. Pla’s world is tranquil and balanced, devoid of great contrasts and provocations although he does occasionally take liberties in his depictions of women and his beach scenes reveal his fascination with children’s excited play. However, through everyday contexts he presents domestic harmony in a pure state, a happy untroubled world – joie de vivre identified with the simple and commonplace. In his sketches he seems to highlight all these features, transforming people into silhouettes of colour and movement, expressionless figures that suggest moods, habits and customs, a collective rather than an individual psychology.

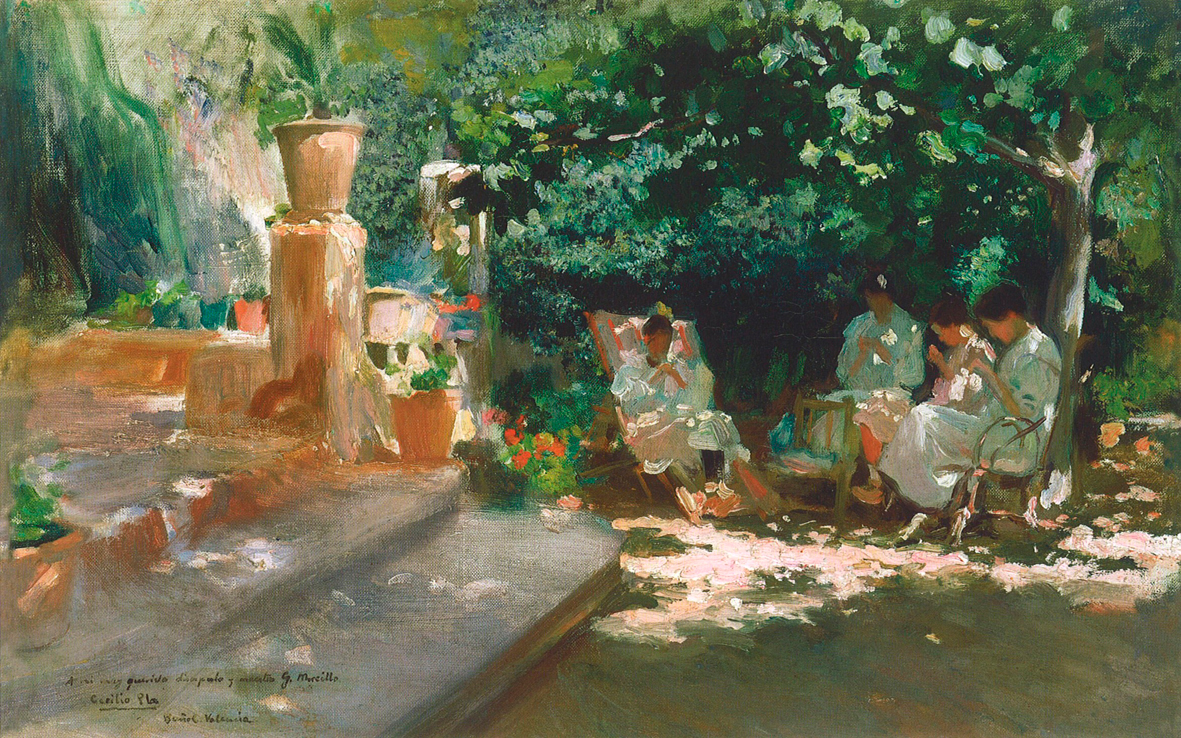

At the foot of some garden steps, a group of women sitting on chairs concentrate on their needlework, as we can tell by their arms and inclined heads. The four figures sheltered in the cool shade of dense vegetation on a warm sunny morning are observed by the painter, whose presence has no influence at all on the separate world of the group. In fact, they are like any other feature of the landscape in which they harmoniously sit, forming a whole. The landscape of the garden, representing nature tamed and laid out by man, is considerably domestic, almost a genre scene in itself thanks to the presence of the four women. Cecilio Pla was particularly fond of portraying intimate family scenes, gatherings on the beach or in gardens, as they helped him to capture the pace of everyday life, the poetry of the moment encompassed by the relaxation of a siesta, the joy of bathing or other leisurely summer activities such as women sewing more for enjoyment to pass the while than to reflect their industrious spirit. For both Sorolla and Pla, as for many other painters of the period, women in the early 20th century resting on a beach or in a garden would still mechanically do handiwork associated with their sex (crochet or needlework), i.e. light activities that required no special concentration and calmed mind and spirit by banishing all cares, repressing anxiety and unease, and dispelling boredom. In Pla's paintings women seldom appear reading books. The education of a young lady from the bourgeoisie in 1900 was reduced to needlework, piano playing and, occasionally, painting – Pla’s own daughter Pepita indulged in the latter. The arrangement of the figures is hierarchical: the three on the right are seated on chairs or wickerwork armchairs, the first slightly lounging, while the figure on the left sits separate from the others on a deckchair. Revealing a leg covered in a black stocking, she appears to be the most respectable of them all, and could possibly be the mother, for we have no doubt that the group is the artist’s family. Sitters and painter all enjoy the beauty and charms of the setting, the former delighting in the actual atmosphere and the latter in his contemplation of them.

The group is slightly off centre, but the dark mass of the vegetation marks the preponderance of the central axis, despite the presence of a path to the right and that of the steps to the left adorned with countless flowerpots. One of these stands on a pillar and marks a vertical line matching the trunk of the tree on the right, and the two vertical lines frame the women, thereby producing a double effect of a peaceful open space. Another feature is the compact mass of vegetation and figures with the empty area of the steps. The picture contains elements from almost all Pla’s sketches, but its vision is more placid and the composition more elaborate. As it was a less dynamic scene, the painter managed to recreate the various details and suggestions without resorting to the dense or broken brushstrokes that characterised his paintings of bathers. He now preferred the technique of the sketch, its paused time. Broadly speaking, he employed two kinds of brushstroke: one smaller and denser and defining the whole of the centre, the foliage and figures, and another longer and informal to suggest and close the background on the left in the typically concise fashion of this type of painting. The canvas, therefore, is halfway between a bozzetto (a sort of rough outline the artist made great use of, many of which were sold) and a more elaborate composition, as revealed by the size, support and scene depicted. The paint was applied directly onto the canvas with no preparatory drawing; the artist’s handling of oils is particularly skilful when it comes to suggesting and animating a wide range of outdoor scenes. Pla, whose drawing skills were excellent and who also displayed extraordinary talent as an illustrator, tackled landscapes and small outdoor scenes in a different, lighter and more free-flowing way that expressed a savoir faire in the use of colour as great as with pencil.

The picture, as we learn from the dedication, was painted in Buñol, a village close to Valencia where people from the capital would often spend the summer, being as it was higher up and therefore cooler in the evenings. Furthermore, the work is dedicated to one of Pla’s favourite pupils and friends, the painter Gabriel Morcillo from Granada. Most of his pupils were from Andalusia and from Granada especially, and López Mezquita and Gabriel Morcillo were perhaps the two he felt the proudest of.

Francisco Javier Pérez Rojas