Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida

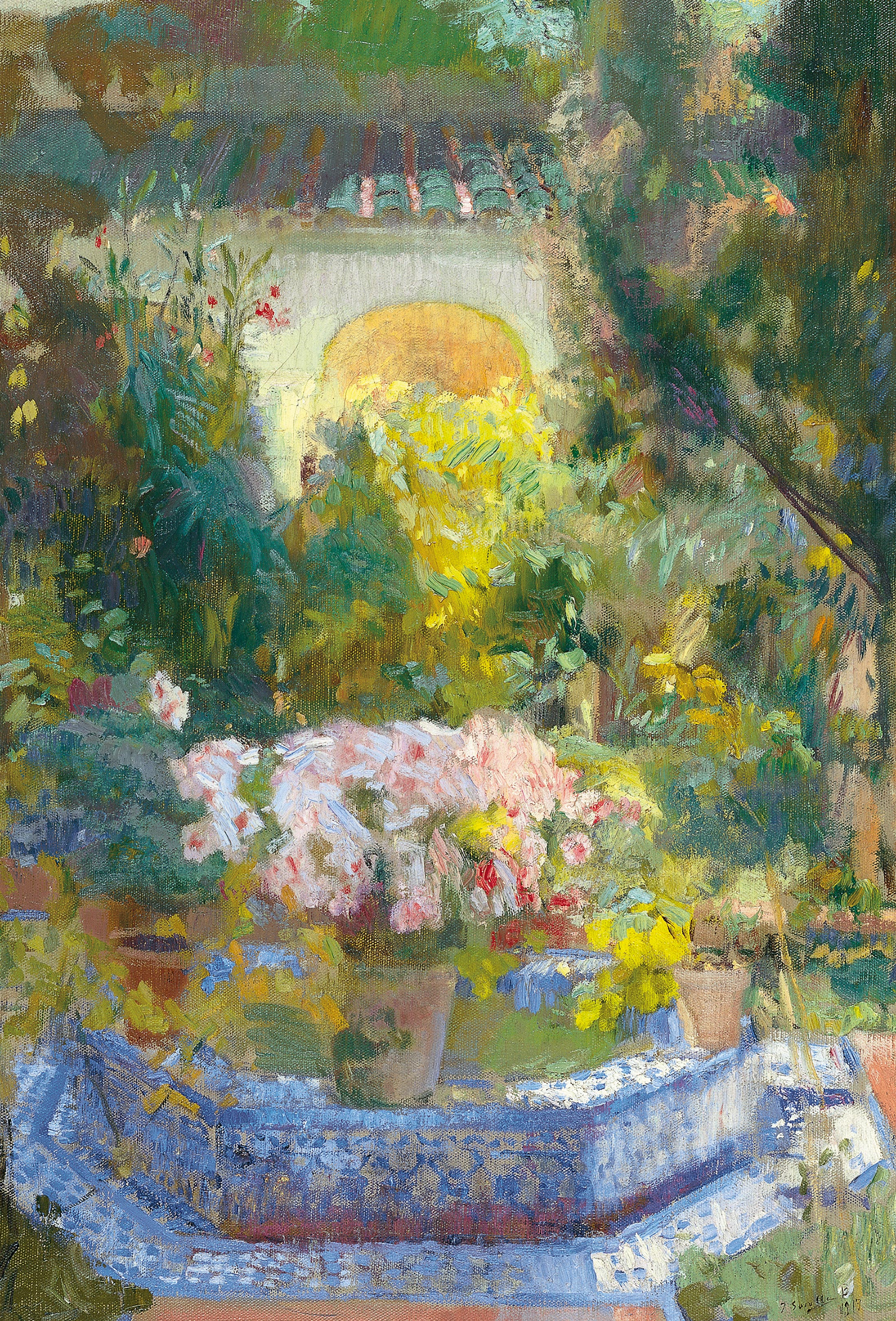

Courtyard of the Casa Sorolla

1917-

Oil on canvas

95.9 x 64.8 cm

CTB.1996.16

-

© Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza en préstamo gratuito al Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga

In 1909 Sorolla invested most of the money he had earned at his New York exhibition in building a house that he himself had designed. Following the advice of his friend, the painter Aureliano de Beruete, he bought a plot of land in the highest part of Madrid – between the Chamberí district and the Paseo de la Castellana or Paseo del Obelisco, as it was then known.

The house was built to plans by the architect Enrique María Repullés. Sorolla himself designed the surrounding garden, greatly in the Valencian and Sevillian styles. He decorated it with fountains and statues, arranged with a great sense of harmony, and with a beautiful collection of Valencian tiles of blue on a white background. The house was finished in 1911.

This painting belongs to a series of studies which Sorolla did of the garden and patios of his house in Madrid. Although most are neither dated nor signed, it is known that they were painted between 1914 and 1920, at different times of the day and in all seasons. However, the garden was mainly depicted in the spring, when the flowers were in full bloom. Bernardino de Pantorba catalogued the twenty-eight views which belong to the Museo Sorolla in Madrid. The others belong to private collections.

In 1917, Sorolla worked intensively on his major series The Regions of Spain, commissioned by Archer Milton Huntington for the Hispanic Society of America Library in New York. However, between February and October of that year, he interrupted his travels through Spain and returned to Madrid, one reason being the birth of his first grandchild. He also took the opportunity to spend the summer in San Sebastián. Courtyard of the Casa Sorolla was no doubt painted in the spring of that year, during his stay in Madrid.

Most striking when one sees this painting for the first time is the colour. The artist displayed his skill in rendering the effect of light with broad brushstrokes. The colours he chose for this picture were those he used in his landscapes and seascapes: yellows, reds and violets. The brushstrokes are uneven, but never unsteady. This is how, a few months after completing this painting, Sorolla explained his particular technique to a French newspaper reporter: “I do not have a recipe, because in my opinion painting is a mental disposition. My brushstrokes are short or long depending on the subject and the occasion.”

The composition is centred on the polygonal blue-tiled fountain covered in flowers and surrounded by abundant vegetation, with part of the house visible in the background. However, the play of colours is so dominant that the spectator pays little attention to the objects represented. Sorolla did not use an iconographic message whose language would be made up of the fountain, the flowerpots, the flowers or the building; his sole interest lay in the surfaces of all of these objects and the way they reflected the prevailing light. Thus, the painting struck a balance between the solidity of the objects, the brightness of the light and the coloured environment in which these are immersed. The vibrant image conveys such an impression of movement within the composition that the light effect on the objects is perceived more clearly than their actual physical solidity.

That year (1917) a number of Catalan critics commented on the connection between Sorolla’s studies and research carried out by Catalan artists such as Anglada-Camarasa, Santiago Rusiñol and Eliseu Meifrèn. But for Sorolla the thorough approach to the study of nature that he undertook in that period was more than a mere visual exercise. Indeed, it often involved strong, and sometimes exhausting, emotions. In 1916 he wrote to his wife: “I don't know whether it's due to weakness or to an excess of sensitivity, but today the contemplation of nature has affected me more than any other day.” And again in 1918, in another letter to his wife, he wrote: “I wish I was not so overcome by emotion because, after a few hours like today’s, I feel devastated, exhausted; I cannot take so much pleasure, I cannot bear it as I used to [...]. This is because painting, when one feels it, is superior to anything else. No, I meant to say it’s nature which is so beautiful.”7 When we gaze at this picture, we are captivated by the painter’s emotional response to nature and charmed by his skill at conveying this emotion through light and colour.

Carmen Gracia